My research for this post got started when I added a genuine rarity to the HOTG archives in the last year or so. It’s a one-sided promo 45 by the New Orleans group, Blackmale - erroneously shown as “Blackmail” on the record, released on the Moneytown label. It was unfamiliar to me then; but as soon as I saw the New Orleans point of origin, band name, and Gerald Tillman as the songwriter, I knew it was a noteworthy record that could help shed more light on the city’s funk scene during the 1970s, and hopefully Tillman himself.

I had long known the name of New Orleans keyboardist, composer and vocalist Gerald Tillman (born in 1955), called “Professor Shorthair” by his friends and admirers, in association with the Neville Brothers. He was listed as organist on their eponymous 1978 debut LP and had posthumous writing credits for two songs on their later albums: “Family Groove” (co-writer) appeared on their 1991 LP/CD of the same name, and“Shake Your Tambourine” led off Live On Planet Earth, released in 1994. Onstage over the years, Cyril Neville has regularly acknowledged Tillman as an influence and inspiration, and also did so in more detail for the collective autobiography, The Brothers Neville, which is where I first learned the details of the important early connection Blackmale had to the brothers as a group.

In addition to the Blackmale track, I’m featuring three other songs, one Tillman played on, one he participated in to some degree, and one he co-wrote. Choices are limited, since not many recordings of his work were ever released commercially. Tragically, he passed away in 1986, cutting short his accomplishments. Very little has been written about him or his contributions to the New Orleans music scene. So, If you knew Gerald, played music with him, or saw him perform during the dozen or so years prior to his demise, feel free to leave a comment or email me. As always, I’d be glad to work more direct information into this post.

[Note: Background research comes from a number of sources, many of which were provided or suggested to me by Jon Tyler, longtime Neville Brothers archiver and keeper of theNevilleTracks blog. He deserves big props for the years of work he has done combining and clarifying the many musical connections of the band and the various, ever-increasing Neville family members. Jon shared with me the text of a brief elegy to Gerald Tillman, written by George Green with Boo Browning, that appeared on an early version of the Neville Brothers website. It contains some helpful facts and clues. He also alerted me to both the YouTube videos linked in this post, let me hear some helpful archival audio, and gave me several other good leads. As already mentioned, some further information on Tillman and Blackmale can be found in The Brothers Neville (Little Brown, 2000). Also, I have relied on two interviews with Ivan Neville I found in which he recalls Gerald:Ivan Neville: Return of the Prodigal Sonby Bunny Mattherws in OffBeat from 2005, andanother by Alison Fensterstockon nola.com in 2010. Most of the rest of the factoids herein come from my archives and various online resources......]On The Possible Makings of A Professor

![]()

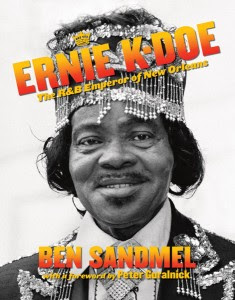

New Orleans being a city of musical families often spanning several generations, it’s not surprising that there is a possible lineage linking Gerald Tillman to some earlier players of note. As I learned from the elegy to Gerald noted above, his father, Joe Tillman, was a saxophonist. In fact, a comment I read by Ivan Neville, who was in the original Uptown Allstars with Gerald in the early 1980s, said that Joe Tillman played sax in their band back then. Fans of early 1950s New Orleans R&B may well recall that there was a well-known sax man in those days named Joe Tillman (pictured), who played on records by Ray Charles, Guitar Slim, Lloyd Lambert, and Joe Turner, among others. Since he was born in 1905 and died in 1976, the elder Joe was the right age to have been Gerald’s grandfather, which would make Gerald’s dad his junior. I haven’t found any corroboration for this as yet, but do recall Cyril Neville remarking in the autobiography that Gerald could blow a mean sax himself.

As long as we’re speculating, I’ll offer up two other older musicians with the same last name who could also have been related to Gerald: Wilbert Tillman played sax, along with trumpet and sousaphone in various New Orleans brass bands from the 1930s to the 1950s; and Eddie Tillman was a bass player who worked on the West Coast in the 1950s and 1960s, recording with Little Richard and Sam Cooke, among others, as Mac Rebennack recalled in Under A Hoodoo Moon..

Such a background certainly might have contributed to the multi-talented Gerald Tillman being acknowledged by his peers as a “professor” while still young. Many of the musicians he collaborated with over the years still cite his influence on their writing and playing, and.It’s almost a given that if you grew up in the Crescent City area, your musical roots run deep. But, leaving conjecture behind, let’s explore what there is to know about Gerald from the music he made and the company he kept. Blackmale: The Beginnings

In funk guitarist Renard Poché’s notes to his 2009 CD,4u 4Me, the title song co-written with Gerald, he includes two fragments of unreleased recordings by Blackmale and briefly reflects on the beginnings of the band and his career in New Orleans. In 1973, Renard (born in 1956) and his bassist brother, Roger, began playing music with Gerald. The teenaged friends started a band that it seems was first called the Bold Souls; but, within the next year or so, the name changed to Blackmale [also shown as Black Male in other sources; but Renard renders it without a space, as does theirpublicity photoon his website]. Joined by drummer Newton Mossop, Jr, they were a highly funkified outfit in a Meters configuration led by Gerald on organ, before expanding to include another keyboardist/vocalist, Gerald ‘Buffalo’ Trinity, and Chris Phillips on percussion. [At least one other player of note briefly passed through Blackmale along the way, keyboardist and Colorado transplant Johnny Magnie, who later co-founded several other significant local groups, Lil Queenie & the Percolators, the Continental Drifters, and much later, the subdudes.]

Blackmale’s lone single appeared in 1974 or 1975. I’ve seen a photo of another promo copy with 1974 handwritten on the label, but Poché dates the release at 1975, which may refer to the two-sided commercial single. That it came out on Moneytown at first raised questions, when I learned that the imprint was not originally local and had been inactive since the mid-1960s. But, as it turns out, the label made a brief comeback just for Blackmale. [Those not interested in the more minute details of record-making lore can just skip the next paragraph.]

George Redman started the independent label, Moneytown Records [not associated with a label of the same name out of Washington, DC some years later] in Chicago around 1963; and it appears there were several even more limited offshoots, Moneytree and Bluelight. After the first Moneytown single, which featured the Desires, a vocal group, failed to get noticed, nothing else appeared on the label until 1965. That year Redman issued five more 45s by just two groups, the Mandells and the Intensions, but had no success with any of them, though some were re-issued by outside lables. He closed down the operation the next year and moved to New Orleans around 1970, where he would later come into contact with Blackmale. Obviously impressed by the band and its prospects, he revived Moneytown and issued their single; but Redman’s venture probably lacked the funds to adequately promote and distribute the record beyond a handful of promo copies and a limited pressing of the single. So, there would not have been much of a chance for it to be heard, and there was no follow-up. As far as I can tell, Redman had one other New Orleans adventure in label ownership somewhat later, Super City, releasing aone-off single(#70115), “Wonders of the World”/”It’s You Baby (It’s You)” by a group named Sex. Leo Nocentelli wrote both songs and co-produced the sessions with Redman; but the Sex project amounted to no more than an unproductive quickie.

As I said, the promotional version of the Blackmale single had only one cut, "Let's Get At It", which at least left DJs no question about what to play, or ignore. But, according to the two discographies of Moneytown I have consulted, the stock copy had a flip side, "Be For Real", which Gerald supposedly also wrote. On the commercial release, the band’s name seems to have been corrected to Blackmale, too; but I’ve never seen even a photo of that 45.. So, if anybody has the record, please let me know. I’d love to verify the details and hear the long lost B-side.

![]()

Blackmail [sic], Moneytown 707-A, 1974-75

As the track reveals, Blackmale was a solidly syncopating outfit with a distinctive sound capable of making them stand out in a town rife with funky bands. It’s also evident right off that there were more than four instruments in play. Along with the drums, bass and guitar, no fewer than three keyboards can be heard: a prominent clavinet, with a piano and Tillman’s organ farther back in the mix. Whether Gerald overdubbed the additional parts or there were other players involved, such as Gerald Trinity, can’t be known without some further authoritative information. [Again, feel free to contact me.]

Mossop played a fairly open, simple drum groove on “Let’s Get At It”, allowing room for the other instruments in the nicely interlocking arrangement to make their own contributions. The result is a tight and at points densely polyrhythmic music bed with each part distinct and engaging. Prime evidence of the hip skills of all involved.

I can only assume that Professor Shorthair sang lead on his own song, which isn’t melodic enough to reveal his range; but the vocalist navigated the intricate lyrical phrasing with a spontaneous ease.

Blackmale had no other known releases, but continued local club work over the next several years, until an invitation came along that altered their trajectory.

The Neville Brothers Connection

Gerald was a genius. . . . He was younger than me, but where I was still searching for it, Professor Shorthair had found it. . . . He taught me more about songwriting than anyone.-

Cyril Neville in The Brothers Neville

He was the glue that kept the brothers' band kicking, and he was an inspiration and a teacher to me.- Ivan Neville on Gerald Tillman, nola.com/Times Picayune interview by Alison Fensterstock, 2010

In 1976. all four Neville brothers, Art, Charles, Aaron, and Cyril, recorded together for the first time, when they made an album of Mardi Gras Indian-related songs with their uncle, George Landry, who was Big Chief Jolly of the Wild Tchoupitoulas. With instrumental backing mainly by the Meters,The Wild Tchoupitoulasnot only was a critical success; but, even more crucial, it sold fairly well. As a result, Art and Cyril quit the conflicted Meters the next year to go out on the road with their brothers and Big Chief Jolly’s gang in support of the record. That joint endeavor proved to be a unifying turning point for the talented family,.with Aaron’s 18 year old son, Ivan, a keyboardist, and Charles’ vocalist daughter, Charmaine, being included in the ensemble.

Art wanted the new aggregation to have a cooking hometown rhythm section to lay down authentically funky grooves on their shows and recruited the core of Blackmale - Tillman, Mossop, and the Poché’s - after catching them in action one night. An extended engagement was booked for the Neville Brothers/Wild Tchoupitoulas at the Bijou Theater, a music venue in Dallas, Texas, during the summer of 1977. It lasted a month or more and provided a vital shakedown cruise that helped establish the group’s identity and sound, laying a foundation for the 30+ years that the Neville Brothers’ have made music together.

I’ve heard a live recording (probably a soundboard tape) from a performance they did in September that year at the Monterey Jazz Festival, soon after the Bijou run, that verifies how impressive and recognizable the group’s sound was even then. At that point, the set list was mostly a collection of cover tunes, leading up to the Wild Tchoupitoulas material closing out the show; but, as Cyril put it, everything they did was “Neville-ized”. Though far from home, the convergence of the brothers’ talents and Blackmale’s booty-loosening ways elicited cheers from the enthusiastic festival crowd and must have been sweet validation for the group’s chosen path. [Looks like aCD of that recordingmay still be available through Charles Neville’s website, or check with the Louisiana Music Factory.]

As 1978 rolled around, the Neville Brothers attracted the interest of a major label, Capitol Records, and went to work making their debut album at Studio In The Country in Bogalusa, Louisiana, with a well-respected pop and rock producer, Jack Nitzsche, in charge. As often happens with such a recording deal, by mutual consent the band’s live sound was moderated for the record in hopes of garnering broader mainstream appeal. So, while there was some grooving and a few references to New Orleans culture, the tracks weren’t nearly as Neville-ized as their live material, and the Mardi Gras Indians were nowhere to be found.

Other than the brothers themselves, only a few of the band members were used on the sessions. Mossop played throughout; and Tillman was listed as organist, though barely used. The Poché brothers were missing, however. Instead, on bass was Eugene Synegal, who had played guitar behind Aaron and Cyril in Sam Henry’s band, the Soul Machine, around 1970. Handling the guitar duties for the album were Jimmie ‘Balls’ Ballero (a member of Aaron’s previous band, Renegade), Casey Kelly (a/k/a Danny Cohen) from Baton Rouge, and L.A. session man Tony Berg, who also arranged the horns.

While the execution was flawless on a mix of material, mainly slow to mid-tempo originals and tunes by outside writers such as Lieber & Stoller and John Hiatt, by design The Neville Brotherswas unable to convey the group's core identity. Not surprisingly, none of the songs in the collection found a long-term place in the group’s live repertoire.

The only number on the LP with an identifiable organ is a trippy, soulful space hymn [reflecting Art’s interest in science fiction, I suppose] on which Professor Shorthair demonstrated some of his Hammond B-3 handiwork.

from The Neville Brothers, Capitol, 1978

After ensemble playing throughout the first three quarters of the tune; the long rideout gave Gerald a chance to trade tasty licks with Art’s electric piano. While certainly no cutting contest, their interaction was as close to an extended jam as the band got on the entire record.

Once the album was released, Capitol seemed incapable of understanding where the material might fit among the already highly segmented commercial radio formats Maybe their best shot at airplay, Lieber & Stoller’s uptempo“Dancin’ Jones”, an enjoyable, funk-tinged blend of uptempo rock and soul leading-off the LP, was simply not pushed, which pretty much ditched the project’s chances of getting heard anywhere but college radio, and ensured a quick end to their recording relationship.

Veterans of the business, the Neville Brothers and band shrugged it off and continued on with their gigging, doing what they did best live. What the record label had seen as drawbacks were actually the group’s assets, roots music with a New Orleans spin full of undulating grooves that filled dancefloors night after night. to the delight of their followers. Their local audiences were primarily the white, college-age crowd in the Uptown area of the city where Tulane and Loyola universities were located. Those enthusiastic partiers frequented the nearby music venues, such as the Boot, Benny’s Bar, the Maple Leaf, Jed’s, Jimmy’s and Tipitina’s, where the band regularly found work. As a consequence, the group’s popularity spread via the word of satisfied customers exposed to the persuasive impact of the soulful funk..

The intervening couple of years without a record contract proved transitional. The brothers began to move away from performing the Wild Tchoupitoulas material due to the deteriorating health of Big Chief Jolly, who passed away in 1980. As their songwriting evolved and repertoire grew; they put out a very limited edition single on their own Cookie micro-label in 1979, with“Dance Your Blues Away”, a near-disco dancer written by Ivan and Reggie Cummings, and R&B groover "Sweet Honey Dripper” written by Art.. I’m still looking for a copy of that I can afford, but having heard both sides, I don’t think Gerald participated on the sessions.

On the bandstand, the young professor remained with the group, along with his Blackmale mates, Mossop and Renard Poché; but Roger Poché was replaced by a new bassist around 1978.. For reference, here is a glimpse of the band in 1979 playing at Jimmy’s on Willow Street in Uptown New Orleans.

[As I learned recently from Jon Tyler, no sound was recorded on the original film footage. The audio medley you hear was taken from other live performances by the band around same time and added during the digital video conversion process.]

As for the players visible, that’s Art, of course, on the left with Ivan and Gerald (in the hat) behind him. To their right, on bass is James ‘Hutch’ Hutchinson, who Art first met in Austin Texas a few years before, while still in the Meters.[ A Massachusetts native, Hutch had spent some time in New Orleans in the 1960s, and was living in Austin when recruited for Neville Brothers by Art and Charles around the time the first LP came out.] That is Aaron, front stage center, with Mossop (I assume) briefly visible on the trap set behind him. Cyril is on congas to the far right, in front of Renard Poché (also hatted). Charles is nowhere to be seen.

1979 was the year that I first saw the Neville Brothers play. I was in New Orleans visiting a friend, who took me to see them at Jed’s on Oak Street, just a few blocks over from Jimmy’s. As I have mentioned before somewhere, it was a revelatory night. The place was packed; and I was, let’s say, in a very receptive state of mind. The greasy, uplifting grooves had me so wrapped up that I couldn’t leave until the music stopped at the end of the night, causing us to miss the last streetcar. The line-up I saw should have been close, if not identical, to the one on film, which means that I likely caught Professor Shorthair in performance in his prime, though at the time I was not familiar with anyone on the stage other than Art and Aaron. Having missed the opportunity to see the Meters live earlier in that era, my first experience of the Neville Brothers band made up for the deficit and put me on the meandering track that eventually led to this blog.

Sitting In With Zig & Gaboon's Gang

Meanwhile, Ivan and Gerald also played keyboards on the side in Gaboon’s Gang, a fleeting band fronted by former Meters’ drummer Zigaboo Modeliste that was chock full o’ funky players. Although I never caught them live, in 2009 Zig put out a five song CD of a 1980 set they did at the Saenger Theatre in downtown New Orleans. It’s calledFunk Me Hardand can still be purchased. Other members that night included Nick Daniels on bass, Melton Cozy on congas, guitarists Teddy Royal and Nelson Reed, with additional vocalists Reggie Cummings and Earl Smith.

Zig and Gaboon's Gang put out one 45 at the time, a true obscurity itself, but no lost gem, sorry to say. Released soon after the live date, it has a place in a subset of records particular to New Orleans, Saints rally songs. Over the years, various local artists, well-known and not so, have written and/or released tunes geared towards firing up fans of the city's beloved but frequently hapless (at least until the Sean Payton era) NFL team. Of course, all have hopes the number might catch on and be played at the games and on the radio during the season, and just maybe sell a Superdome full of copies. But even local favorites such as Dr. John, Aaron Neville, Irma Thomas, or Zig never could quiie get the tunes to function as intended.

![]()

"Let's Get Fired Up"(J. Modeliste)

Zig and Goboon's Gang, Orleans International Ltd 001, 1980

Unfortunately, the song on both sides of the record had the shallow production ambience of a low-budget advertising jingle; but there was some good playing going on, especially the hot soloing by an unknown saxophonist and guitarist. I have nothing solid on who played the session, but assume at least some members of the live band participated. Studio instrumentation differed somewhat from the live show; which had no horns. Ivan could very well have played clavinet here, since it was his specialty with the Neville Brothers and Uptown Allstars; but with no other keyboards to be heard, if Gerald was on the track, he would have been singing back-up. [Update via Jon Tyler: Nick Daniels has confirmed that he, Zig, Ivan, and Gerald played on the single.]

For a song by one of the funkiest drummers on the planet, the beats come off as rather one dimensional and (dare I say it) machine-made, they are so repetitive and undynamic. The groove is an upbeat boogie driven by the forceful, upfront bass riffing and pumping (Daniels), reinforced by the rest of the rhythm section. But it's a stretch to say this record could have made anybody break much of a sweat. In contrast, the live version on that CD was a far, far funkier, high caloric keeper. Had it been packaged instead and played inside the Dome, those Who Dats would have risen up as one to shake what their mamas gave 'em, and the energy expended might have really inspired dem Saints. Too bad.

Once the record tanked, Gaboon's Gang didn't last too long. Then, out of the crew that played the Saenger gig with Zig, four came together on Professor Shorthair’s next project.

The Rise of the Uptown Allstars

The exact date of the formation of the band that Gerald christened the Uptown Allstars is not clear, but seems to have been around the time that the Neville Brothers recorded their second LP, Fiyo On the Bayou, in 1980-81. Through the intercession of Bette Midler, a fan with influence, A&M Records gave the brothers an album deal; and the sessions took place at Studio In The Country and Sea-Saint. The making of the record, which I’ve touched on before, is a tale in itself; but suffice it to say here that the producer, Joel Dorn, another influential friend of the brothers, for whatever reasons decided not to have the stage band participate, opting instead for seasoned session musicians, a mix of locals, mainly from the Sea-Saint roster, and some imported from the big leagues out of town.

It appears that Gerald conceived theUptown Allstars around 1981 as a continuation of the original Blackmale, setting up the collaborative funk unit to play out when the brothers weren't doing shows. Joining him from the earlier band were Gerald Trinity and Renard Poché, along with new recruits Ivan Neville, Nick Daniels, Reggie Cummings, and drummer 'Mean’ Willie Green - all formidable players just coming into their own. Benny’s Bar, on the corner of Valence and Camp in the same Uptown neighborhood where the Neville brothers grew up, became the Allstars’ home base.

After the release of Fiyo in the summer of 1981, the Neville Brothers toured for a while to support it. Their biggest coup was getting to open for the Rolling Stones on selected dates of the huge Tattoo You tour across the US that fall. While the exposure considerably upped their profile, sales of the album again came up short, despite it being a far better representation of the group that got raves from critics, musicians, and the band's small but fervent fanbase. The next year brought big changes in the backing band, as Tillman, Poché, Hutchinson, and Mossop stepped aside.

In September of 1982, the Neville Brothers recorded a weekend of live shows at Tipitinas, with songwriter and bassist Darryl Johnson, guitarist Brian Stolz, Willie Green, and Ivan comprising the revamped supporting rhythm section. The recordings were released over the next few years on two worthwhile LPs, Nevillization on Black Top, and Nevillization II (Live at Tipitina’s) on Spindletop. Connections between the bands remained, though, with Willie keeping his place in the Allstars, as did Ivan, albeit briefly.

Ivan Leaves For L.A.

Also around 1982-83, Ivan met members of the band Rufus at a Neville Brothers gig in New Orleans and gave them a demo tape of some of his original material. Having parted ways with soul-diva Chaka Khan several years earlier, Rufus invited Ivan out to the West Coast to audition for a vocalist slot on a new album in the making.with producer George Duke. Duly impressed, they gave Ivan the green light to sing lead on about half the LP's tracks, including a song he had written with two compadres from the Allstars.

![]() “The Time Is Right”(Ivan Neville, Gerald Tillman, Nick Daniels, III)

“The Time Is Right”(Ivan Neville, Gerald Tillman, Nick Daniels, III)Rufus, from Seal In Red, Warner Bros, 1983

I would bet this tune was on the tape Ivan gave to Rufus, and was originally intended for the Allstars, seeing as Tillman and Daniels were co-writers. Built around the prominent, hooky bass riffs of each section, the music was all about the strong, cyclical groove. The lyrics may have been insubstantial, but Ivan delivered them with soulful intensity, locked in with full rhythmic focus.

The album’s production feel reflected what was hot commercially at the time: slick, post-disco, urban contemporary funk and soul - everything in its place and precisely rendered with that highly synthesized instrumentation and electronically processed sonic sheen so valued by radio program directors. To his credit, Duke made sure that this track had hardcore, polyrhythmic dynamics impossible to ignore, even if rendered in the digital abstract. The airbrushed sonics proved an odd juxtaposition for Ivan’s singing here and on his other tracks, since his voice has such a natural rough husk to it. But the contrast actually makes his featured vocals the most appealing of the lot. He grounded the songs he sang, smearing the polish just a bit, and brought hints of the New Orleans street into play. I’m really impressed with how well he handled his role, seeing as he was just in his early 20s and it was his first venture into music industry machine. Working with an established, mainstream, hit-making band bolstered by the cream of West Coast studio musicians, and a well-respected musician/producer, he needed to be at the top of his game, and did not disappoint.

As for it’s appeal with the record-buying public,Seal In Redhad only mediocre results, barely rising into the top 50 before a rapid descent. The one track pulled from it for radio play didn’t have Ivan up front, depriving him of a true shot at a national audience. With no more than a half-hearted push by the record company, the album lacked legs and turned out to be the last full Rufus studio release. Ivan had moved on by the time the group reunited briefly with Chaka later in 1983 for a big farewell concert captured on the double LP; Stompin’ At the Savoy - Live, that ironically was a big hit.

Back on the home front, the Neville Brothers covered “The Time Is Right” on their shows for several years after the album came out, giving it their own far more organic funk feel; but Ivan was rarely around to sing it. After his work with Rufus, he stayed in L.A., making more contacts in the music scene and soon hooking up again with Hutch Hutchinson, who had gotten there ahead of him and been hired to play in Bonnie Raitt’s band. When Bonnie needed a keyboard player for her next tour, Ivan had an inside edge and got the call, working with her steadily for several years. After that, he wound up in New York City, was befriended by Keith Richards and Ronnie Woods, made an appearance on the Stones' Dirty Work album (on bass!), played in Keith’s side band, the X Pensive Winos, and later launched his own solo career, having learned well from his time in the family band and working with Professor Shorthair.

Following Ivan’s departure from the Uptown Allstars, his uncle Cyril took over the band, and began moving their material into a mixture of New Orleans second line street beats, reggae, and some Caribbean soca with original songs that often addressed his outspoken worldview.. I’m not sure if Tillman totally left the band at that point, but I know he worked with several other outfits through the early to mid 80s, including Satisfaction, headed by guitarist Red Priest, who played regularly around New Orleans and regionally. Yet another of Tillman’s own projects, G. T. and the Trustees, also involved the Neville Brothers’ prime funk movers: Willie Green, Darryl Johnson, and Cyril.

The Final Days of Professor Shorthair....and Beyond

In 1986, Gerald headed out to L.A. to work with Ivan, Nick Daniels, Leo Nocentelli, and Reggie Cummings on original tracks for his own album project, but became ill and had to return home. On September 15th that year, he passed away, just 31 years old. With a largely untapped potential, his creative gifts never became well-known to the world beyond his hometown, but surely would have been given more time.

A few days after his passing, an all night jam was held at Benny’s Bar where his friends, family and fans celebrated Professor Shorthair’s life and positive influence that still resonates in the music of the peers he inspired.

Besides the songs mentioned earlier that were later recorded by the Neville Brothers and Renard Poché, several other examples of his writing have surfaced since his passing.

One is a mystery track, “Be Your Number One”, on Irene Cara’s 1987 album,Carasmatic, with songwriting credits to Gerald Tillman, Yolanda Smith, and Harold Allen, Jr. I have not found a listing for this song in the US Copyright or BMI databases, nor any firm information on the other writers. Any suggestions?

Ivan Neville included two songs on his 1995Thanksalbum: “Hell To Tell”, which he co-wrote with Reggie Cummings and Gerald, and “Padlock”, written by Gerald alone.

Also, the monster cut,“Deeper”, written by the two Geralds, Tillman and Trinity, was recorded by Ivan’s band, Dumpstaphunk, in 2010 appearing on their Everybody Want Sum CD. Among the other outstanding musicians in the group is original Uptown Allstars alum Daniels, who helps them keep Shorthair’s legacy alive and very deeply funkified.

Finally, I’ll leave you withthis linkto a brief, poignant glimpse of the man himself performing solo at Tipitina’s just a few weeks before he left this world behind.